- Home

- Johnny D. Boggs

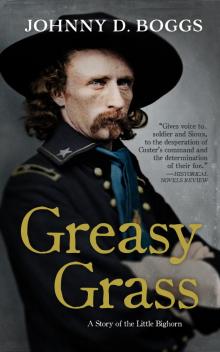

Greasy Grass

Greasy Grass Read online

GREASY

GRASS

A Story of the Little BigHorn

JOHNNY D. BOGGS

Copyright © 2013 by Johnny D. Boggs

E-book published in 2018 by Blackstone Publishing

All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

Trade e-book ISBN 978-1-5047-8798-7

Library e-book ISBN 978-1-5047-8797-0

Fiction/Westerns

CIP data for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Blackstone Publishing

31 Mistletoe Rd.

Ashland, OR 97520

www.BlackstonePublishing.com

For Errol Flynn and Richard Mulligan;

Otto Becker and Thom Ross;

Evan S. Connell and Joseph M. Marshall III;

Thomas Berger and Quentin Reynolds;

Comanche and Crazy Horse.

“I feel sorry that too many were killed on each side,

but when Indians must fight, they must.”

—Sitting Bull

“Oh what a slaughter how Manny homes Made

desolate by the Sad disaster eavery one of them were

Scalped and otherwise Mutiliated but the General, he

lay with a smile on his face the indians eaven

respected the great Chief.”

—Private Thomas Coleman

“What kind of war is it, where if we kill

the enemy it is death; if he kills us it is a massacre?”

—Wendell Phillips

Preface

At the time of his death, George Custer was a brevet major general, but his actual Seventh Cavalry rank was lieutenant colonel. Military etiquette, however, allowed officers to be addressed by their brevet rank. Hence, in this novel, army officers are often called by their brevet rank (Colonel, instead of Captain, Frederick Benteen; Lieutenant Colonel Myles Keogh; Major Tom Custer). I chose to go with the brevets to be historically accurate.

Likewise, for historical accuracy, I’ve opted to spell the river Little Bighorn. Some sources often write Bighorn—there’s about as much disagreement over the spelling today as there is on all other aspects of the battle—but in 1876, the most common spelling was Little Bighorn.

Finally, an Indian in South Dakota once told me and other journalists: “Never call me a Sioux. That is a name given our people by our enemies. I am Lakota.” I haven’t forgotten that. Sioux comes from the French Canadian Nadoüessioüak, or Nadouessioux. White characters in this novel might refer to those Indians as Sioux, but when using the Indian point of view, I have generally opted for Indian names.

A short glossary is at the end of this book for your reference.

1926

Prologue

Libbie Custer

Fifty years have passed since my darling Autie, my love, my husband, my inspiration, was called to Glory, yet despite the aches (of aging bones and five decades of loneliness), I feel as if it happened only yesterday.

New York City is two thousand miles and twenty million memories away from the Little Bighorn in Montana, but today it feels closer. Too close.

Tears fill my eighty-four-year-old eyes as I sit in the sun room of the Doral Hotel and listen to the radio. The radio announcer’s voice squeaks that he sees an airplane flying over the battlefield, but I can’t hear the motor. Now, the voice tells me and millions of other listeners that William S. Hart, the great actor of those Western moving-picture shows, is among the tens of thousands of people in attendance. Fourteen thousand automobiles line the road leading to the battlefield where my dashing, gallant Autie—and nigh three hundred other brave Americans—breathed their last. Automobiles and flying machines! I wonder what Autie would think of that had he lived, if he were on the Little Bighorn this day, watching the festivities.

Watching? Hardly. Not my love. No, George Armstrong Custer would not be standing on that hill, scarlet neckerchief flapping in the wind. Not the dashing boy who once, riding a spirited horse during the Grand Review of the Army of the Potomac, bolted down Pennsylvania Avenue and passed General Grant at the head of the parade, right in front of the White House. Autie claimed that his horse had been spooked by a thrown bouquet of flowers, but I, and General Grant, knew better. On the other hand, were it not for Autie, such a parade might have been held in Richmond, Virginia, in 1865, rather than in our nation’s capital. No, Autie would not be watching, standing still. He would be flying that biplane, swooping down from the skies, laughing wildly as he frightened the tourists, dignitaries, and Indians on the ground.

Now, I can hear music as the announcer begs us to listen for a moment. Recognizing the funeral march, I sigh, and dab my eyes with a handkerchief. They should be playing “Garry Owen,” Autie’s favorite song, the song of the Seventh Cavalry.

The announcer now describes the terrain, a land I have never seen except in my mind, my nightmares. Only once did I even come close, begging Captain Marsh of the Far West to take me with him just a few days after Autie had marched away, but Captain Marsh would not allow me to steam into harm’s way.

Oh, I was invited to this grand fiftieth celebration, and considered traveling the long distance, stopping in Monroe, Michigan, but I could not acquiesce. It was my age, I told them, and how could they argue with a white-haired widow who has nothing but memories and a cherished name?

Yet I did not decline on account of my age. I could not feel my heart break again, and surely it would were I to stand beside the marker where Autie—and Tom, his brave, tortured brother … and young Boston, another brother, always the butt of Tom’s and Autie’s jokes … and Jimmi Calhoun, my sister-in-law’s husband … and Myles Keogh, that gallant Irishman of sad songs and sadder eyes … and sweet William Cooke with his flowing dundrearies … and our nephew Harry Reed, just eighteen years old, who carried Autie’s nickname—fell.

The dirge has ended. Here in Manhattan, cars crawl and pedestrians hurry about their business, oblivious to this momentous day. Yet inside the sun-room, I feel the heat of the Montana summer. The announcer speaks again, excited. He can see the Seventh Cavalry, coming from the southeast, led on this day not by the fabled Boy General, but Colonel Fitzhugh Lee and retired Brigadier General Edward Godfrey. The radio falls silent. No words are necessary. Wind rustles across the microphone. I close my eyes. I see the Seventh, clear as day, but not being led by Colonel Lee and wonderful, kind, courageous General Godfrey.

I see Autie.

I see myself.

We are not at the place the savages call the Greasy Grass, but rather at Fort Abraham Lincoln along the Missouri River in Dakota Territory.

* * * * *

The morning of May 17, 1876, dawned gloomy at the fort. A thick, foreboding mist hugged the waterlogged quagmire that once had been a parade ground. In all my twelve married years, I had seen Autie prepare to march to battle, yet never had I felt like this. I cried, and even he could not comfort me. “I just can’t help it,” I told him again and again, sobbing my final words, “I wish Grant hadn’t let you go.”

President Grant had, however, and Autie, ever the child, could not contain his excitement about this campaign. A great present for our country, he thought, on our centennial celebration. He acted like a boy eagerly awaiting Christmas or his birthday. Happy as I’d ever seen him, while my heart failed me.

“You must be brave,” he told me. “Come.” He kissed the tears off my cheeks, and led me outside into the gloom, which matched my mood.

We joined Maggie, Autie’s sister, wife of Lieutenant James Calhoun—Jimm

i to us—and were assisted onto our horses, for we had been allowed the privilege—or perhaps it was a curse—to accompany the soldiers on that first day’s march.

“Garry Owen” played as we slogged through the mud and muck. Then “The Girl I Left behind Me.” Through tear-filled eyes, I looked at the other wives watching from the shadows of the buildings. I felt their pain, for it must be the same as mine. Some held their little children in outstretched arms, letting them watch their fathers ride off. The wives knew, but their children did not, that this might be the last time they were to see those brave young soldiers.

Soon, we passed the Indians, the peaceful ones, the families of the scouts who rode with the Seventh. Some of the old ones, men and women, sang that awful wail—so unlike “Garry Owen”—while the women, the wives, busied themselves with their work. Or maybe, as I think back on it now, they did not want to watch their husbands ride to their deaths.

At the point, I rode with Autie, and as we crested the first true hillside, I turned to watch horses, men, wagons—twelve hundred soldiers, seventeen hundred animals in all—stretching two miles long. Then … I saw it.

The sun rose higher now, hotter, the last remnants of the fog burning off but still some mist hanging in the air overhead. Off this mist reflected a mirage, a premonition, an omen. I could see the soldiers of the Seventh marching.

Marching on the earth. Marching in the sky.

Toward heaven.

Lips trembling, tears streaming again, I turned my horse, and caught up with Autie. The band’s music had been replaced by the sounds of a campaign. Sabers rattling. Leather squeaking. Traces jingling. Wagons rattling. Hoofs slurping through muck. No one spoke.

That evening, we camped along the Heart River. The paymaster paid the soldiers. The soldiers paid the sutler, who wanted all debts settled before our boys rode off on one of the biggest Indian campaigns in our nation’s history. Autie and I retired to our tent for our last evening together. The next morning, I clutched Autie as tightly as I could, and cried again. He practically pried my arms off his neck and told me that all would be well, that Custer’s luck had never failed him, that if he died a soldier’s death, so be it.

Thusly the Seventh marched to destiny, and Maggie and I returned to Fort Abraham Lincoln with the paymaster … to wait, the most unholy, inhumane task for a soldier’s wife.

Daily I wrote Autie letters, to be mailed on the steamers. Nightly I cried.

* * * * *

The radio voice is talking again, almost in a church-like whisper, but I cannot hear.

I am thinking to that Sunday exactly fifty years ago.

* * * * *

Fort Abraham Lincoln fell quiet after a startling “Reveille.” Twenty-five mounted Indians were spotted, but, as it turned out, this was not a raiding party, for all of those savages had reservation passes. So the day transpired without fanfare. The troopers left behind were likely still condemning themselves at the hog ranches like My Lady’s Bowery or the Dew Drop Inn on the banks of the Missouri. There was no baseball game to be played, for the first nine and the muffins of the Benteen Baseball Club were somewhere in Montana Territory with their backstabbing coach and commander, Captain Frederick Benteen, a lout and wastrel.

After church, the ladies of the Seventh met in my home. We sang hymns, but “Nearer My God to Thee” could not comfort us. In fact, when I suggested that we sing it, Emma Reed choked, “Not that one, dear.”

Eventually, Katie Gibson could no longer strike a chord on the piano, so she simply sat there, head bowed, staring at the ebonies and ivories in profound silence. Poor Maggie lay on the carpet, sobbing into the pillowed lap of Annie Yates.

The lemon cookies Katie had baked for us were tasteless; the tea I brewed, bitter. The Bible passages Annie tried to read offered no solace.

I closed my eyes, and thought of Autie. I forgave him of his transgressions. I pleaded for God to absolve me of mine. Just let me see Autie again; let his beard scratch my face as he kisses me. Let me give him a son to continue his name.

Forcing a smile, I hugged my guests before they departed to the doleful and solitude of their homes. I listened to “Taps” and prepared myself for another sleepless night.

That evening, I went to bed a widow.

But did not know it.

1876

Chapter One

Boston Custer

Almost twenty-eight years old, yet Tom and Autie still treat me like a kid. If you go by their immature actions, however, they are the children.

God blessed Tom and Autie with good health and glory. On the other hand, like big brother Nevin, I was cursed and saddled with asthma. No West Point. No wars. No medals. Unlike Nevin, however, I refused to become a farmer, and Autie allowed me to accompany the Seventh Cavalry as a forage master when we explored the Black Hills two years ago. Now I ride with my brothers, and nephew Harry Reed, against the red heathens. I am assigned as a packer and forager, though I prefer the assignments as guide and scout.

I do not shirk my duties. I do my work. I do not complain. Often, since I am also a “guide” and “scout,” I leave the pack train and ride at the head of the command with Autie. Better still, I even accompany my brothers on their “scouts.” Yet this is what happens when you are the youngest brother, when you do not have two Medals of Honor (as brother Tom earned during the late Rebellion) or the legend of George Armstrong Custer.

On May 31, two weeks after our departure from Fort Abraham Lincoln, Tom, Autie, and I rode out on what Autie called a scout, but in actuality was nothing more than a lark as we explored these badlands near the Little Missouri River. Alas, my horse picked up a pebble, forcing me to dismount, unfold my pocket knife, and begin freeing the stone embedded in its left forehoof. Would my brothers wait for me in hostile Indian country? No. Of course not. Abandoning me to my chore, they disappeared over the hill.

Finally I found myself back in the saddle. The air had turned cold, yet I sweated. Not even a breath of wind found its way between the rough ridges through which I rode. I knew better than to cry out for Tom or Autie, fearing some red devil would hear my voice and disembowel me, for we had already pushed to the edge of Dakota Territory and neared Montana Territory and its hostile Sioux and Cheyennes.

Visions of such savages had just entered my mind when a gunshot rang out. Another. Another. One bullet whined off a rock several rods to my left.

Heart pounding, I wheeled my horse, raking army-issue spurs over its flanks, feeling the mare’s power as it exploded into a gallop, for this beast of burden was as terrified as I.

Leaning low in the saddle, I topped the ridge, turned more northwestward, thinking that might bring me to the safety of our column sooner. The biting wind now blasted my face. My straw hat flew off. I wanted to reach for my revolver, but could not loosen my grip on the reins. Then the most fearful sounds reached my ears.

Hoof beats. Right behind me.

“Come on!” I cried out to my mount. “Run, confound you, run!”

The horse stumbled, almost flung me over its neck, but both of us righted our balance. Somehow, I managed to release my grip on the reins with one hand, and pounded the horse’s side.

“Faster! Faster!”

We reached a hill, and I leaned forward, urging the mare up. I wanted to look behind me, but could not summon the courage, fearful of those fiendish painted faces. As the horse picked its path up the hill, the wind stopped again, and I heard a new sound.

Laughter.

Immediately my face flushed red, and I turned the gelding to spot my big, brave brothers sitting in their saddles, laughing, pointing. Tom, having dropped his reins across his mount’s neck, carried my hat in his left hand. Autie swung down, almost doubling over with laughter as he tried three times to thrust the reins into Tom’s free hand before he managed. As I eased down the ridge, Tom extended my hat toward me. By that time, A

utie had dropped to one knee, laughing that belly laugh of his, wiping his eyes with the end of his scarlet neckwear.

“Bos,” Tom said as I eased my mare toward him, “I don’t know what Autie and I would do if we did not have you to tease so.”

I snatched the hat, and jerked it on my head. “Why not pull your pranks on Harry Reed?” I demanded.

“He’s … too … young.” Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, brevet major general, hero of Gettysburg, Trevilian Station, Winchester, and the Washita, my big brother, snorted.

“He is standing this trip first-rate,” I said.

“But he’s not our brother,” Tom said.

Autie managed to stand and take the reins from Tom. He patted my thigh, then sniffed, and turned to Tom again. “Do you smell something?” Autie asked.

“Do you mean … like a … latrine?” Tom queried.

They both stared at me.

“Check your pants, Mister Custer,” Autie said in his most commanding voice.

I replied with a most indelicate suggestion, turned my mount, and loped away from my two brothers, whose howls tormented me as I rode up the hill.

* * * * *

I concede feeling my own taste of victory—or perhaps revenge—that afternoon, when, upon our return to the column, Colonel Custer himself met with a severe rebuking from our commanding officer, General Alfred Terry.

For while my brother was off scouting with Tom and myself, General Terry had managed to have lost his entire command.

Lost!

Well, it is quite easy in this harsh wasteland.

“Without any authority,” the general scolded, “you left the column. This is not a game, Custer. It is a military operation, the most important of your, and my, career.”

“I thought I could be more service to you, General, and the column, acting with the advance,” Autie replied, rather humbly for him, like a punished child. A lie, of course. I doubt if either Tom or Autie even looked for Indian sign.

The Fall of Abilene

The Fall of Abilene A Thousand Texas Longhorns

A Thousand Texas Longhorns MacKinnon

MacKinnon Hard Way Out of Hell

Hard Way Out of Hell Buckskin, Bloomers, and Me

Buckskin, Bloomers, and Me Hard Winter

Hard Winter Wreaths of Glory

Wreaths of Glory Whiskey Kills

Whiskey Kills Doubtful Canon

Doubtful Canon West Texas Kill

West Texas Kill The Killing Shot

The Killing Shot Greasy Grass

Greasy Grass Kill the Indian

Kill the Indian Return to Red River

Return to Red River Northfield

Northfield And There I’ll Be a Soldier

And There I’ll Be a Soldier The Raven's Honor

The Raven's Honor Summer of the Star

Summer of the Star South by Southwest

South by Southwest Mojave

Mojave Valley of Fire

Valley of Fire The Cane Creek Regulators

The Cane Creek Regulators