- Home

- Johnny D. Boggs

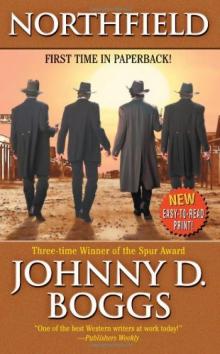

Northfield

Northfield Read online

NORTHFIELD

Johnny D.

Boggs

LEISURE BOOKS NEW YORK CITY

For Tyrone Power and Henry Fonda;

Ron Hansen and Max McCoy;

John Newman Edwards and Jack Koblas;

Red Shuttleworth and W.C. Jameson;

The people of Northfield and Madelia;

And The Friends of the James Farm.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue: Cole Younger

Chapter One - Bill Stiles

Chapter Two - Adelbert Ames

Chapter Three - Clell Miller

Chapter Four - Joe Brown

Chapter Five - Mollie Ellsworth

Chapter Six - Colonel Thomas Vought

Chapter Seven - Jim Younger

Chapter Eight - Alonzo E. Bunker

Chapter Nine - Anselm R. Manning

Chapter Ten - Charlie Pitts

Chapter Eleven - Cole Younger

Chapter Twelve - John Oleson

Chapter Thirteen - Henry Mason Wheeler

Chapter Fourteen - Lizzie May Heywood

Chapter Fifteen - Frank Jupies

Chapter Sixteen - Thomas Jefferson Dunning

Chapter Seventeen - Jesse James

Chapter Eighteen - A.O. Sorbel

Chapter Nineteen - Sheriff James Glispin

Chapter Twenty - Bob Younger

Chapter Twenty-One - William Wallace Murphy

Chapter Twenty-Two - Dr. Sidney Mosher

Chapter Twenty-Three - Sheriff Ara Burton

Epilogue: Cole Younger

Author’s Note

About the Author

Praise

Other Leisure books by Johnny D. Boggs

Copyright

PROLOGUE

COLE YOUNGER

Seven minutes…seems like seven lifetimes.

“For God’s sake, boys, hurry up! They’re shooting us all to pieces!”

The words still ring in my head, over the deafening roar of musketry. Over the bullets singing past our heads. Over the hoofs of our horses. Over all of Northfield.

Those words came from my mouth only minutes earlier. Long minutes, though. Think about it—seven minutes ain’t nothing. Time it takes a train to cover a little better than two miles. Time it takes me to deal an interesting hand of stud. But those seven minutes that just passed….

Biting back pain, I still picture myself banging on the door of the First National Bank, snapping off shots with my .44 Russian at city folk we figured would have no gumption to stick with a fight.

“For God’s sake, come out! It’s getting too hot for us!”

By then, I figured it was too late. Knowed it was too late for poor Clell Miller and Bill Chadwell, or whatever his name was, dead on the streets, their souls meeting up with St. Peter. Knowed it was too late for me. And my brothers. That’s what I was regretting then, what I still regret now. Bob and Jim have always looked up to me, most times, anyway.

What strikes me, what shames me, what terrifies me ain’t the thought of dying, but I see Brother Dick, shaking his head, more than disappointed. Behind him, I can just make out Pa’s face. And Ma’s. Both of ’em crying. The image humbles this old soul.

I ain’t the oldest of us Jackson County Youngers. Brother Dick, he was the good one, the best of us all, the first son of fourteen children, him entering this world six years before me. Three girls come before him, and two after him and before me. Had God been merciful, things might have turned out different for my family. Dick got a gut ailment, though, pained his side something fierce—quick it was, though, so there’s some blessing—calling him to Glory when I was but fifteen. Dick’s death killed Pa, really. Or would have. But the war come, bringing with it every freebooter who spit on a Missouri man’s rights, and I followed my heart, same, me thinks, as Dick would have. Then them murdering sons-of-bitches put three slugs in my daddy in June of ’62, tossed his body in a ditch, like trash.

The war—that killed Mama, only there was no blessing to that. Pa and Dick, they didn’t suffer none, but Ma, she just wore out, and with cutthroats chasing me because of my loyalties during the war, and all the torment, she just give up. We had moved her to Texas, but I reckon she knowed she was dying, maybe she wanted to die, so she asked for us to take her back to Jackson County, to be near our pa. She joined Pa, been six years now, and how I miss her. I see her crying. I feel shamed, for all the misery I caused her on earth, and now up on those streets of gold.

“Thomas ‘Bud’ Coleman Younger is a killer,” they say. A bushwhacker. A murderer. A robber and black-heart. A soulless guerilla. A man who ain’t fit to breathe. Well, let he who is without sin cast the first stone.

Yankees made me an outlaw, a bushwhacker, but I’m just a simple farmer fighting for my family, my home, my honor, my brothers.

I should have looked after ’em.

Thoughts like that haunt me as I ride. My brother’s arm tightens across my stomach, then slips.

“Hold on, Bob!” I cry.

“For God’s…sake…don’t…leave me.” His words come out as he chokes, coughs. He’s bad hurt, but he ain’t dead…yet.

“I ain’t leaving you, Bob!” My horse stumbles. No Missouri horse, but I sure can’t fault his spirit. Horse has gotten us this far. Bob, riding behind me, almost lets go. He’s whimpering now, like he was on the streets back yonder. I ain’t got no reins. Ain’t got a horn left on the saddle to hold on to. Got nothing but Missouri mettle, and a strong desire to get my brother out of here alive. Somehow.

“For God’s…sake…don’t…leave me!”

Seven minutes…and everything had gone to hell.

“Which way?” Charlie Pitts screams.

“Just ride, damn it!” Dingus shouts back. “Ride or get buried!”

We ride. Six men on five horses. I don’t know how long we can hold out.

Now, I’ve made some mistakes in my thirty-two years. Always owned up to ’em, most of ’em, anyway What happened at Lawrence back in ’63 never should have happened, though nobody— not Rebel, not Yankee, not Redleg or Jayhawker, not Quaker nor freethinker—can ever say I did anything during that raid that should cause me to hang my head. Not in my book, by grab. I wisht it never happened, but the Lord can’t damn me for anything I did on that horrible day all them years ago.

That was Kansas, though, and this ain’t, not by a damned sight.

We never should have come to Yankeedom. Not now, no matter how bad things kept getting in Missouri. Certainly never should have tried to steal that carpetbagging son-of-a-bitch Silver Spoons Butler’s money.

Biggest mistake of my life, coming here. North-field, Minnesota. Our trail’s end, could be, and there ain’t nobody to blame but me. I should have known better. Only reason I come along is because of Brother Bob. Stubborn, he is, wouldn’t listen to men. Wouldn’t hear nothing Jim said, either.

Should have made Bob listen, only he thinks Dingus is cut from the same cloth as Pa, or Captain Quantrill. Should have pounded sense into Bob’s head, or just pounded him. He never could whip me. And, Buck, my old pal, I don’t know what he was thinking.

That damned Dingus.

He’s the one who should have been left dead on the street in Northfield. Not Chadwell. Especially not Clell, as true a friend as they come.

If Dingus wasn’t Buck’s brother, maybe I would have killed him.

Still, I don’t reckon I can fault him. Dingus and me may have our differences, but, like I said, it’s me to blame. It’s a cross I’ll carry to my grave. I’m just praying I ain’t buried in a land of Yankees.

CHAPTER ONE

BILL STILES

Sounded like a damned tent re

vival meeting. People’ll tell you that Bill Stiles ain’t a man accustomed to fear. Hell, up in St. Paul just a few years back, on a bet I fought a bulldog in the street. Dog ripped me up pretty good, but I killed that shit-eating cur with my bare hands, won me $10 and a jug of applejack. But the time I tell about, I got me one damned bad feeling.

’Twas Jesse’s idea to rob the Missouri Pacific that July night, though Frank done all the figuring. Those who knew Jesse longer called him Dingus, but I always called him Jesse or Jess. Likewise, Frank’s pards called him Buck, but I never called him nothing. Just didn’t care for him none is all. He was too highfalutin for my ways, quoting Shakespeare and the Bible all the time, or getting into them dumb debates about religion and war with Cole. Cole, they called Bud, while I called him a self-righteous bastard, only not to his damned face. Cole or Bud, Frank or Buck, Jesse or Dingus. Names don’t mean much when you’re an outlaw. Fact is several of the boys all knew me as Bill Chadwell. It’s the handle I use when I’m down South.

Like I said, Frank done the figuring and, I’ll give him this, he figured things pretty good. The No. 4 Express left Kansas City for St. Louis with a big payload, and Frank knew the spot to hit it was at Rocky Cut. Railroaders was building a bridge over the Laramie River, and trains had to slow down real safe-like to get through this gash. Dangersome it was, so damned wicked the Missouri Pacific put a night watchman along the cut with a red lantern so he could help guide the engineer through.

Perfect place for a robbery, Frank said, and it turned out to be exactly that, but even Frank couldn’t figure on some damned preacher.

First thing we done was capture the watchman, him begging for his worthless life, then Clell Miller and Charlie Pitts began piling railroad ties on the track, just to make sure the train would stop, while Bob Younger tied and gagged the sobbing watchman.

Cole, Frank, and Jesse stayed on the banks of the cut, watching for the train and any laws or Pinkertons, while me and Hobbs Kerry hung out a ways back. Once the train come past us, me and Hobbs hurriedly dragged ties and timbers on the tracks and had that train snared like a rabbit. Didn’t have nowheres to go.

Once the train stopped, things got noisy, us filling the night sky with lead and cusses, firing our six-shooters in the air like the bushwhackers we was. Rebel yells and bullets put the fear of God in everyone in railroad coaches and express cars, especial down in Missouri in 1876. Went off pretty damned good. Not like that first robbery I pulled with the boys back in ’73 when we just derailed the damned train in Iowa. Killed the son-of-a-bitching engineer, and almost left a passel of others dead or bad maimed, and got away with $2,000 from the strongbox, plus about half as much from the pickings of the passengers. What a disaster that was. Christ! Oh, the money was fine, and the killing didn’t bother me none, but we just couldn’t find the bullion aboard—three and a half tons. Had we made that score, I guarantee you we wouldn’t have been at Rocky Cut. Least, I wouldn’t have been there.

But this was all right, the Rocky Cut robbery, till we went through the passenger cars, and that preacher started praying. Not no brimstone. No, he was too damned scared to sound like some hard-shell Baptist. Kept praying for God’s mercy, that their lives would all be spared, but me and Clell figured he was only interested in saving his own sorry-ass life.

Now, the boys and me don’t go about killing no innocent people, so they didn’t have a damned thing to fear. We wasn’t scared, neither. Only person aboard with any backbone was a boy—some green pea who tried to pull this little pocket pistol on us when Clell robbed his concession chest. That struck me as damned funny, especially when Clell took the gun from the kid, who started yelling at us, tears in his eyes but showing grit.

“Hear that little son-of-a-bitch bark,” said Clell, laughing as he went to the next car to relieve them damned passengers of their money and things.

But, Jesus, this preacher! Once he finished praying, he started leading them travelers in singing. Hymn after hymn they sang, in the dead of night, while Frank and Cole worked on the express boxes and Jesse stood guard.

I went to the horses, to spell Hobbs Kerry, half a mind to mount up and ride away, forsaking my damned share. Glad I didn’t now, but damned if I wasn’t spooked by that God-blasted singing. “‘Lock of ages, cleft for me.’”

It troubled me, I tell you. Pitch black night but for the lights from the train. Hardly a noise except the hissing locomotive. Horses even kept quiet. But the singing. Frightened voices, singing to God.

Hell, I shivered, and that got Hobbs Kerry to cackling.

“Someone step on your grave, Bill?” he says.

“Why don’t you just go back to your damned coal mine!” I barked back at him, and that shut up his damned fool mouth.

Cole and the James boys jumped down from the express car, Jesse having his fun. “Good night, gentleman. Thanks for the business. We’ll see y’all again sometime soon.” And Cole, always trying to be so damned respectful, calling out to the baggage master: “Watch yourself, Mister Conkling! Tell the engineer the tracks are blocked fore and aft. Best clear them before y’all go on your way.”

I untied the night watchman’s gag and binds, then mounted up. Easy as you please, we rode out, laughing, while that congregation in the middle coach just kept singing them damned hymns. Wasn’t quite midnight.

Around dawn, we reined up to give our horses a rest, and pass out the shares.

“Mighty fine haul, Buck,” Cole said to Frank as he emptied the wheat sacks.

“‘A feast is made for laughter,’” Frank replied, “‘and wine maketh merry…but money answereth all things.’”

That’s why I wasn’t on friendly terms with Frank. Uppity if you ask me, spouting his damned scripture, showing us that he was an educated man, though he ain’t.

Cole was right, though. Was a damned fine haul. Bet we made off with better than $15,000. Jesse rolled a wad and shoved the greenbacks in his trouser pocket. He come over to me, slapping me on my back, and laughing.

“We’ll be traveling to Minnesota in style, eh, Bill?”

Minnesota was my idea, which Jesse took to like a catfish to stink bait. It was Jesse who brung me into the gang all them years ago, sided with me even though Frank and Cole suspicioned me to my face and called me a Yankee. Jesse, he’d back me all the way, told me so, and, when I said maybe we should head north and rob them Minnesota banks, steal bona-fide Yankee money for a change, he loved the plan. My plan.

“Them banks are just full of cash up there,” I said. “Black-earth farmers and wealthy mills, and that rich carpetbagger governor, I hear tell he run back home after mistreating those damned fine people in Mississippi for so long. They almost impeached that bastard.”

“They should have hung him,” Jesse said.

We was down in Texas when I broached the notion. Jesse didn’t say much more about it, maybe ’cause Cole started acting scornful. That had been in late winter, maybe spring, I disremember, but I won’t forget when Jesse sent word for me, back in Missouri, to meet him at the cave we hid out in around Monegaw Springs. It was early June. He asked me to tell him more about them Minnesota banks.

“I know Minnesota,” I told him, which wasn’t no damned brag. “Banks are rich…richer than anything we see down here. Fat with cash, and them city folks, there ain’t a one of them with any damned sand in their craw. Dumb farmers, town drunks, yellow-bellied businessmen.”

For a spell I’d hung my hat in Monticello, had family still living in Minnesota, and I’d been all over southern Minnesota. Sis, she taught school near about Cannon Falls. She didn’t want much to do with me, especially after I done that spell in the Stillwater prison, but her no-account husband, he sure liked hearing my stories, and I bet I could have him join the boys if he wasn’t so henpecked and Frank and Cole so damned suspicious of anyone from up north.

“Governor Ames, that black-hearted bastard who ruint Mississippi, he and his daddy-in-law, that damyankee General Butler, they got money in

them banks. Shit, Jess, it would be justice to steal from them two thieves.”

“You know the towns?” Jesse asked.

“Sure. Mankato. Albert Lea. Northfield. Faribault. I know them all. Know every slough, every forest, every tree.” I grinned. “Every whorehouse, too.”

Jesse didn’t say nothing.

“Ain’t a man in the state worth a tinker’s damn,” I repeated.

“We’d have to do some scouting,” Jesse said.

My enthusiasm was growing. “Sure, Jess, sure. And Saint Paul, now there’s a city for you. Don’t have to worry about no law there, long as you don’t start trouble. Folks in that town let folks be, and it’s got some fine-looking whores and plenty of card tables.” I let out a good holler. “Jesus Christ, Jesse, it’ll be a vacation for us!”

Well, one of these days I’ll learn. Jesse, his eyes went damned cold, and he lowered his voice, telling me that, if I ever used the Lord’s name in vain around him, he might just shoot me dead. I offered him my apologies, and he said no more on the matter.

Them James boys, they should have been damned preachers.

Next time we met up was in Kansas City, at a hotel. Jesse had done some more thinking, and he wanted to talk it over with Bob Younger. Bob, he couldn’t be much older than twenty, and he thought the world of Jesse. Like I said, I didn’t have much use for Cole, and he none for me, but Bob? Now him I liked. Didn’t know Jim well, one of the other brothers, him off in California, being a respectable farmer or something.

“Minnesota?” Bob said, damned incredulous. “I don’t know, Dingus.”

“You sound like your big brother,” I said, and I mean to tell you, them hairs on Bob Younger’s damned neck stood up. Guess one reason I liked Bob so was that I knew how to play him.

“Cole ain’t my keeper, Bill,” he shot back at me, and Jesse grinned one damned cold grin.

“Yankee money, Bob,” he told his friend. “Bill, here, he knows the land. He’ll guide us through. And the banks there are rich, filthy rich, rich with money stole from good Christian Southerners. It’d be enough for you to buy that farm you got your eyes on, Bob.”

The Fall of Abilene

The Fall of Abilene A Thousand Texas Longhorns

A Thousand Texas Longhorns MacKinnon

MacKinnon Hard Way Out of Hell

Hard Way Out of Hell Buckskin, Bloomers, and Me

Buckskin, Bloomers, and Me Hard Winter

Hard Winter Wreaths of Glory

Wreaths of Glory Whiskey Kills

Whiskey Kills Doubtful Canon

Doubtful Canon West Texas Kill

West Texas Kill The Killing Shot

The Killing Shot Greasy Grass

Greasy Grass Kill the Indian

Kill the Indian Return to Red River

Return to Red River Northfield

Northfield And There I’ll Be a Soldier

And There I’ll Be a Soldier The Raven's Honor

The Raven's Honor Summer of the Star

Summer of the Star South by Southwest

South by Southwest Mojave

Mojave Valley of Fire

Valley of Fire The Cane Creek Regulators

The Cane Creek Regulators